I’ve been observing the minimalist movement for some time now.

I love the concept of a few well chosen, beautifully made items I can treasure, over the commercial churn of the cheap ‘trendy’ junk you see scattered along the roadside at every council clean up.

I wonder if the sign of a truly wealthy society is the lack of waste it produces?

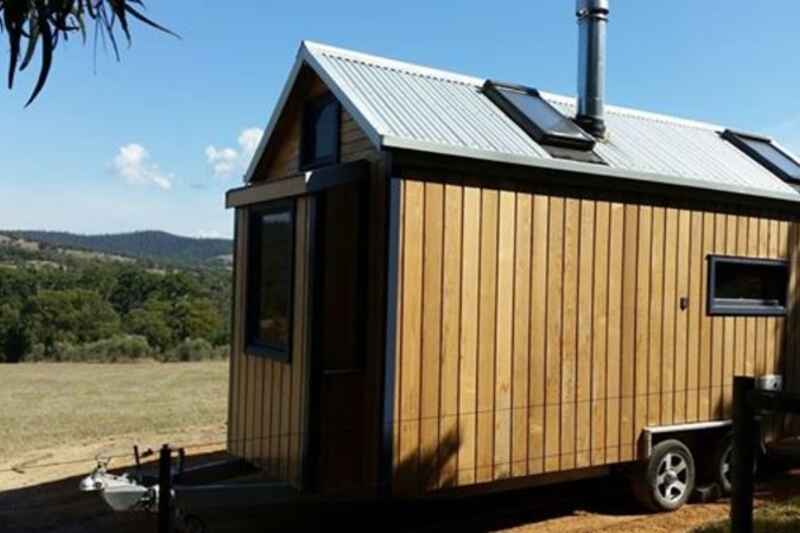

But in terms of living with less, what is fascinating me at the moment is the attention tiny houses are getting – from both sustainability advocates and the architecturally inclined.

While the tiny house movement is thriving overseas, here, it is more of a slow burn. Still, a number of established architects are adding modular tiny houses to their portfolios – and the movement has also spawned tiny house start-ups with architecture graduates at the helm.

Smaller dwellings have always been around, but this latest incarnation seems to have its origins in the USA in the early 2000s, with a surge in popularity after 2008’s global financial crisis.

We've been slower to adopt the trend here in Australia, but our increasing housing affordability problem has created a burgeoning niche for savvy architects to supply the demand for cheaper, more sustainable and even portable homes. And the trend has seen validation in the media (both social and broadcast) – in particular, the ‘reality TV’ series Tiny House Australia.

The polar opposite of sprawling McMansions, tiny houses range in size from 9.5sqm to 37sqm, with small houses somewhat bigger – up to 93sqm. Tiny house designs typically range from cute, portable old-style wood cabins to sleek studios on wheels or ‘micro apartments’ influenced by the 1970s Japanese architectural trend. Then there are the more accommodating ‘small houses’, such as a cleverly designed four-storey “vertical apartment” on a small block in Sydney’s Surry Hills. While ideal for young people and a small family, though, this type of home might not suit an elderly person, as stairs seem the only way of moving between floors.

Modern small and tiny houses are all about clever design, a conscious, deliberate use of space and being mindful of a dwelling’s intended inhabitants.

It's also about sustainability, affordability and energy efficiency. Many dwellings are prefabricated, ready-to-assemble designs, which keeps costs down for low income and first-home buyers. Some small house companies use only sustainable, eco-friendly construction materials, and solar powered utilities, and emphasise these benefits of tiny and small house living in their marketing.

Benefits such as:

• Smart design and use of space

• Green building materials with little or no out-gassing for a healthier home

• Water conservation

• Energy efficiency – solar powered portability

So who would a tiny or small house appeal to – and why?

Not surprisingly, it tends to be people without children: those under 30 and then 50 and over – the 'empty nesters'; perhaps those older people who might otherwise buy a caravan and travel the country.

If you dig deeper into the psychology of it all, it's suggested there's even a personality type that's attracted to living small – those who display two particular psychological traits: clustering, or hanging out with like-minded individuals, and self-verification: a high need for uniqueness and wanting to be seen in ways that align with their identities.

Ask a tiny house devotee what their motivations are, however, and they're likely to list big picture ideals like: a desire to live modestly and off the grid while conserving resources, environmental consciousness, self-sufficiency, and wanting a life of adventure.

The movement remains something of a subculture in Australia, with high land prices, council regulations, building codes and insurance restrictions among the barriers to wider adoption. However this approach to design could help solve the disconnect some suggest exists between how a house occupant wants to use their space and the architect's vision. With so little space, both designer and dweller need to pare down to basics, and the modular form of these homes offers an element of ‘mix and match’ to meet a person's needs.

While you can only be in one room at a time, these economic spaces are not for everyone – living in such close quarters can be a stressor in itself, as anyone who has ever retreated to their own space to escape conflict at home would know. And it's not so practical for families, the elderly or share house arrangements.

Still, there’s no doubting the admirable sustainability consciousness and affordable attraction of tiny houses, and living small does suit many people. Ultimately, it comes down to that well-known architectural principle: form follows function.

Images Courtesy of Murray Goodchild of The Tall Tiny and Stuart Dakin of Tiny House Transition - With thanks